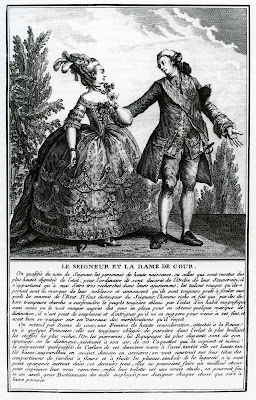

The strict rules for admission of women to eighteenth-century French court required a woman to prove a title of nobility reaching back to 1400 (although special dispensation was made for "favourites" like the King's mistress). The regulation of court dress was a legacy of Louis XIV's plan to bring the aristocracy into line and the guiding rule was "Persons of Quality must now become Persons of Taste". Dress etiquette allowed nobles to visibly demonstrate their place in society and for many, a brilliance of style in dress became their reason for being.

For presentation at court, women had to wear le grand habit de cour (the grand habit). Full court dress consisted of a heavily boned bodice with short sleeves, a full skirt over a large hoop, and a long train. This ensemble was all made of the same fabric, typically silk or satin brocade. The skirt alone typically required 20-25 yards of fabric. Trimmings included lace, ribbons, bows, embroidery, beads, sequins, and sometimes even jewels. A tailleur de corps (always male) made the whale-boned bodice and train, a courturiere made the skirt, and a marchand de mode (like Rose Bertin) provided the trimmings, lace and adornments for the ensemble.

This elaborate and cumbersome gown made it difficult to move gracefully. According to the Marquise de La Tour du Pin the weight of the dress made it impossible to raise the foot in heels three inches high, so the correct movement was to take little gliding steps.

The grand habit was worn for the most formal court occasions such as presentations, balls, baptisms, and marriages of members of the royal family.

Given that Marie Antoinette grew up in a more informal court environment in Vienna, is it any surprise that she rebelled against such rigid dress etiquette and preferred the chemise a la reine, a simple white muslin gown?

(Source: Dress in Eighteenth-Century Europe, by Aileen Ribeiro, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2002).