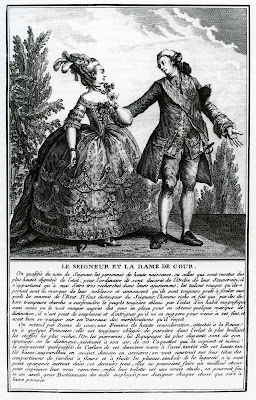

Paris has been the center of fashion since Louis XIV, the Sun King, recognized the symbolism inherent in his sartorial splendor. At the top of the French social hierarchy, the King's luxurious, elaborate and ostentatious clothing and accessories created the impression of power, grandeur and prosperity.

Members of the court were expected to follow the lavish dress of Louis XIV. It was recognized that proper dress could provide access to the King and a courtier by the name of Nicholas Faret wrote in 1636 that "

clothing was one of the most useful expenditures made at court". The importance of dressing fashionably at court fueled the demand for luxury textiles, ribbons, lace, and related accessories.

Louis XIV's finance minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, designed economic policies that capitalized on this demand. Colbert emphasized the expansion of commerce and the production of textile and fashion-related industries in France. He also regulated the guilds that controlled the manufacture and sale of luxury goods.

Guilds were strictly regulated, with strict rules of conduct and quality control. There were approximately 125 different groups associated with dress (Savary de Bruslon's Dictionnaire Universale de Commerce of 1726). These groups could be categorized into three main groups:

1. manufacturers who provided the raw materials (eg., fabrics and trims)

2. craftsmen and women who produced garments and accessories (eg., corset makers, tailors, glove makers, hat makers, fan makers, jewelers, embroiderers)

3. merchants who sold the goods (mercers, drapers, linen merchants, furriers, hosiers)

Over time, mercers became more and more significant in the luxury goods trade in France. Since they were not allowed to manufacturer goods, only to sell finished products, they developed a range of techniques to make their wares more desirable. Items underwent the process of "enjoliver", prettying up, and shops became gathering places for the fashionable elite.

As fashions changed, with less emphasis on the textile itself and more emphasis given to the trims and accessories, fashion merchants became uniquely positioned to meet the needs of their customers. The marchandes de modes rose to the top of the fashion pyramid.

In 1776, when the guilds were restructured, the importance of the marchandes de modes in the merchant trade was recognized and a new separate guild was incorporated. This was one of the few guilds that allowed women.

The best known marchandes de modes is Rose Bertin (born by the name of Marie-Jeanne Bertin in 1747). Even before she was introduced to Marie Antoinette by the Duchess of Chartes in 1774, Bertin was considered a preeminent fashion merchant, and was known for her creativity, especially when it came to hats.

To be continued ....

Photo from Quilts of Provence by Kathryn Berenson

Photo from Quilts of Provence by Kathryn Berenson